Editor's note: Our tulip displays are just beginning to come into bloom. Depending on weather, peak bloom is expected at the end of April/early May. Please check our website and interactive map to see What's in Bloom during your visit.

Every spring, thousands upon thousands of beauty-seekers head to Longwood Gardens to take in one of our most spectacular sights—our beloved tulips. Ever-changing and always stunning, our tulip display is undeniably gorgeous, but what is it about the tulip itself that draws so much attention and wonder? Why are we so attracted to this seemingly simple flower? The answer may go far beyond the tulip’s beauty and instead lie in mankind’s fascination with the unattainable.

Tulipa ‘Zurel’ (single bloom tulip) at Longwood Gardens. Photo by Candie Ward.

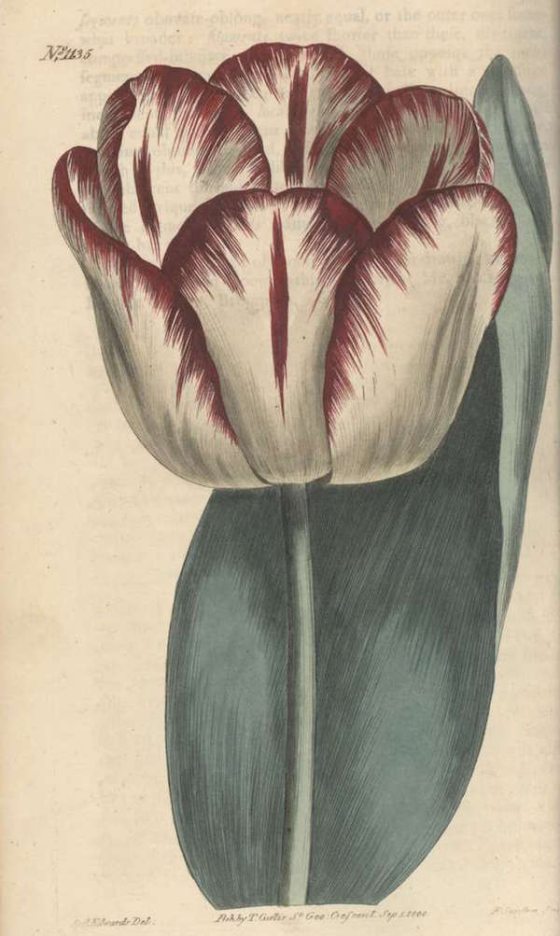

Tulipa gesneriana as shown in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (volume 28, 1808), from the Longwood Gardens Rare Book Collection.

The intriguing story of our fascination with the tulip begins in Ottoman Turkey, where they were first cultivated around the year 1000. Under the rule of Mehmet II, tulips were among the country’s three other classic flowers—rose, hyacinth, and carnation—and appeared on many public buildings and structures. Lines of poetry celebrated the tulip’s wild origin, which spanned southern Europe into central Asia, notably around the Pamir Alai, Tien Shan, and Caucasus Mountains.

As far back as the 11th century, Persian poetry likened tulips to gemstones and even blood, based on the Turkish folk hero Ferhad, who tunneled through a mountain for a decade to gain the love of Sirin. Upon learning his love had passed during that time, Ferhad killed himself with an axe, bright red tulips springing from his blood. To Turkish mystics, the tulip’s Turkish name of lâle consisted of the same letters as hilâl, meaning crescent—the symbol of Turkey—as well as Allah, making the tulip a cultural and religious symbol.

Based on its beauty and cultural reverence, the tulip rose in rank during the mid-16th century under Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, who demanded tulips be embroidered on his gowns and embossed on his horse’s armor. Around that time, Turkish botanists began breeding tulip cultivars from wild forms, and the tulip’s shape—once round and full—became thin and outstretched. As plant scientists discovered that they could transform these scentless flowers through selective breeding, the tulip became more of a status symbol, particularly those new cultivars—in seemingly boundless colors and forms—resulting from experimentation.

The Western world soon took notice of the tulip, where it became known as tulipan, similar to the Turkish word for turban, dülbend—a fitting description, as Turkish flower enthusiasts wore tulips in their turbans and the first Turkish tulips resembled turbans themselves. While mystery remains concerning exactly how tulips made their way to Europe, it’s believed that Oghier Ghislain de Busbecq, the Austrian Ambassador from Ferdinand I to Turkey, sent seeds home to Europe around the year 1550. Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens included tulips in the first edition of his 1568 book of ornamental and fragrant flowers, titled Florum et coronariarum odoratarumque nonnallarum herbarum historia, but Flemish botanist Carolus Clusius is best known for recording Europe’s growing fascination with the tulip, first mentioning them in 1570. Clusius gathered most of his findings while supervising the imperial gardens in Vienna for the Habsburg emperor Maximilian II starting in 1573.

Tulipa ‘Miranda’ (double bloom late tulip) at Longwood Gardens. Photo by Candie Ward.

By the close of the 16th century, dozens of different kinds of tulips had emerged, highlighting the flower’s limitless color palette and its unpredictability. It was this element of chance that led to a quick rise in the popularity of this plant. Growers quickly and excitedly realized that tulips grown from seed did not necessarily resemble their parents and grew enamored with tulips that included “breaks.” These breaks, marked by flaming and streaking of a different color in the petals, were in fact signs of a tulip ailing from an aphid-transmitted virus. Ironically, the condition responsible for such beauty in the blooms led the plants to be short-lived, as the virus would kill the bulb after only a few years.

Tulipa ‘Washington’ (single bloom tulip) demonstrates the color breaking that was so prized by the Dutch.

Plant enthusiasts passed tulip bulbs and seeds to one another as a mark of friendship, and as tulips quickly moved into the commercial sector, their price continually increased. In France, single tulip bulbs were welcomed as dowries by prospective sons-in-law. Tulips were frequently stolen from the gardens of those lucky enough to have them. Those who could not afford the real thing had paintings of tulips commissioned to be hung in their home. Tulips were taking off in a far too rapid, far too nonsensical way.

The rapid and illogical rise of the tulip’s popularity is best demonstrated by Tulipmania, which took hold of Holland from 1633 to 1637. Delirious at the beauty and rarity of certain kinds of tulips—and the wealth that could come from the buying and selling of those rarities—players in the tulip game often traded bulbs sight unseen, frequently to buyers without the money to pay for them. Only the hope that they could sell the plants at a higher price kept the market alive. Prices rose so high that a single Semper augustus bulb commanded enough money to buy a house in Amsterdam, valued at about $35,000 in today’s dollars. As rising prices for rare tulips attracted new players into the market, the tulip trade flourished to the point where Holland contemplated introducing a tax on tulips. In February 1673, however, the unthinkable happened.

When a group of buyers and sellers gathered at an auction in February 1637, the auction quickly failed when nobody bid. Just like that, the tulip trade and its accompanying craze came to a screeching halt. Rumors quickly flew about the tulip trade’s seemingly eminent demise and news of the auction spooked growers, who convened in Amsterdam in hopes of resolving the crisis by annulling all pending tulip contracts. After Holland’s High Court ruled all uncompleted transactions since the beginning of 1636 as invalid, Tulipmania was officially finished.

Interestingly enough, a second wave of tulip fever broke in Ottoman Turkey less than a century later, when the tulip’s beauty and status symbol took hold of Sultan Ahmed III. Under his rule—during which his chief florist set out 20 rules governing the perfect tulip, including that its petals should be long and equal in length, all filaments and blotches concealed, and its stems long and strong—the flower became a sign of extravagance and cultural excess. The sultan even required guests to wear costumes that complemented his tulips while gathering in the garden. Tulip prices rose dramatically and the government issued fixed price lists, until the sultan’s regime was overthrown and, with it, this unstable preoccupation with the tulip as a status symbol.

Tulipa ‘Bright Parrot’ (fringed tulip) at Longwood Gardens. Photo by Longwood Volunteer Photographer.

In its wake, Tulipmania left some in financial woes, but the tulip itself emerged unharmed. It lived on in gardens and paintings of the Dutch Golden Age and began its journey to America in the mid-19th century. In 1923, experts were able to isolate the virus that causes tulips’ color breaks, further ensuring the tulip’s longevity and welfare. Today, tulips with breaks are the result of stable genetic mutations, not a viral infection. The Dutch continued to cultivate tulips and today the tulip trade is again flourishing, with The Netherlands serving as the world’s leading bulb producer by far, and the tulip serving as one of the world’s most popular garden flowers.

Today, here at Longwood, we herald spring’s arrival with 145,000 tulips beautifully displayed along our Flower Garden Walk and in our Idea Garden. We plant hundreds of thousands of bulbs—daffodils, hyacinths, tulips, and more—purchased from Holland each October in preparation for Spring Blooms. The result is a tapestry of more than 200 varieties of gorgeous tulips of all bloom types, including single blooms, double blooms, and fringed, as well as flamed varieties that display the color breaks so prized by the Dutch and have been bred to remain stable. These beauties in nearly every hue create a magnificent display of color, form, and splendor built upon centuries of fascination.

Spring tulips along Flower Garden Walk at Longwood Gardens. Photo by Larry Albee.

Resources

Howell, Catherine Herbert. Flora Mirabilis: How Plants Have Shaped World Knowledge, Health, Wealth, and Beauty, An Illustrated Time Line. Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2009.

Pavord, Anna. The Tulip. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1999.

Potter, Jennifer. Seven Flowers and How They Shaped Our World. New York: The Overlook Press, 2013.