In August 2021, the Longwood Gardens Library received a sizable donation of archival material from the Kennett Library, documenting the lives and stories of the people of Kennett Square— foremost among them the famous author and diplomat Bayard Taylor. Acquired to assist in the interpretation of the Longwood Cemetery, where many Kennett locals are interred, including Bayard Taylor, our first priority for the collection became documenting what was contained within. As Longwood’s Library and Information Services intern this year, the task of sifting through the 41 boxes in the collection and creating a plan for their future organization fell into my lap. An avid lover of history (I earned my bachelor’s in history), I relished the opportunity. Luckily, the Library and Information Services team took detailed notes when acquiring the collection, so most of my work involved checking a spreadsheet and verifying the contents were correctly identified. However, with a collection this large and diverse, there were sure to be some gaps in the inventory list—and one such gap took me on a two-week trip through time.

My work began with a series of 23 monochrome photographs, sandwiched between a stack of newspapers and booklets. My curiosity piqued, I turned them over to find that they had an inscription on the back—in German! A lover of linguistics with a background in German language studies, I had to figure out who had taken these photographs, and why.

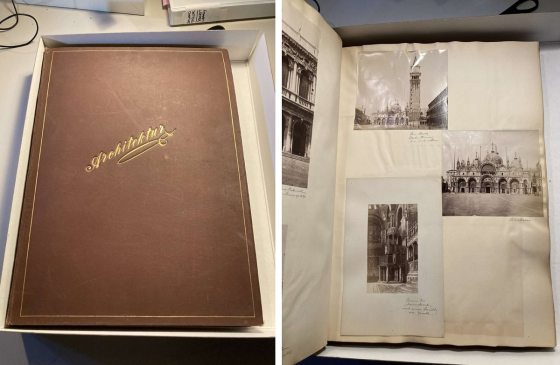

Beyond the fact that they were taken by someone who spoke German, my only starting clue was the location. Based on the inscriptions, all of the photos were taken in Greece, mainly the island of Crete. Before I could pursue that lead, though, another discovery deepened the mystery—an “architecture” scrapbook of postcards and photographs showing historical buildings, dating to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with more inscriptions in German. Was the creator of this scrapbook the same as the photographs? What story were these items trying to tell?

I began researching right away, following two main lines of investigation. The first was an analysis of the handwriting on both the photos and the scrapbook. If they could be matched up, a common author could be established, which would allow me to apply any discovery about one item to the other. The second vein entailed a thorough review of the life and travels of Bayard Taylor. Why Taylor? The Kennett Library, founded in 1896, was dedicated to the famous Kennett Square writer and diplomat, and collected a variety of material by or about Taylor. It also happens that Taylor was fluent in German, and his second wife, Marie Hansen, was a German native. It seemed like a long shot at the time, but it was all I had to work with.

Comparing the handwriting samples was a fairly simple, though time-consuming process. After locating letters that had unique elements, such as uppercase Ps, Gs, etc., examples from both the photographs and scrapbook were laid next to each other and photographed. From there, I uploaded the images to my computer, so they could be manipulated and zoomed in on. The results were encouraging—though the handwriting wasn’t a perfect match, many elements of the letters shared the same quirks. It was likely that the author was the same, probably writing at different times in their life, which could explain the slight differences between the samples.

Confident that the scrapbook and travel photos were created by the same person, the only thing left for me to do was figure out who that person was. Thankfully, the Taylor hypothesis quickly began to gain credence.

The first bit of evidence to suggest the Taylor route was a paper inventory list from the 2000s, which listed items in the Kennett Library Special Collections. Among the items in the Bayard Tayloriana section was a “turn-of-the-century architectural scrapbook,” donated to the library by Bayard Taylor Kiliani, the great grandson of Bayard Taylor. This was undoubtedly the same scrapbook in our collection, and the donor’s identity suggested it must have come from a member of the Taylor family.

Not long after this evidence surfaced connecting the scrapbook to the Taylor family, evidence would surface connecting the Greece photos. Taylor was an avid traveler and a popular travel writer. He published numerous books recounting his trips, including Travels in Greece and Russia, with an excursion to Crete. Contained therein was the story of Bayard and Marie Hansen Taylor’s honeymoon to Greece and Crete, with precise details on where and when the pair went. Scouring through this book, I was able to match location by location the Greece photographs to places the Taylors visited.

Taken into account with the other evidence I’d discovered thus far, it was becoming increasingly likely that the scrapbook and travel photos were made by either Taylor or Hansen; all that remained was proving which one it was. Fortunately, handwriting samples from both can be found online through Harvard Library, which facilitated a second round of comparisons. Unfortunately, this time would prove much more difficult. Unlike the first round, neither the handwriting of Taylor nor Hansen seemed to share many characteristics with the handwriting in our collection. Furthermore, Hansen’s handwriting, who was at the time the leading candidate, was very difficult to read, unlike that of our samples.

Frustrated by a sudden and unexpected roadblock, I devised two possible workarounds. Still confident that Hansen or Taylor were the authors of our mystery items, I attempted first to examine handwriting samples from the breadth of the Taylor’s lives. Handwriting samples can naturally change over a period of several decades, so my hope was that the failure to match up the handwriting was due to the length of time between samples used. This change proved fruitless, with no decade in the couple’s lives providing samples that seemed to match well with the samples in our collection.

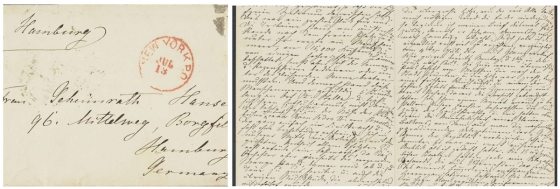

The second workaround was to simply change the source of the handwriting. Up to this point, letters to friends and family had served as the source of samples, which tended to be longer in length and form than the short inscriptions in our collection. Thinking that the length or purpose of the writing might change its appearance, I sought shorter, more deliberate writing samples. With this second method, things were back on track. A few items in Harvard’s collection included not just letters, but also the envelopes they were sent in. The handwriting on envelopes were much clearer and more deliberate in their form, and in looking at these, the familiar characteristics identified in the handwriting samples from our collection began to surface. Specifically, it was the handwriting of Hansen which matched up almost perfectly to our handwriting samples.

Just as research was wrapping up, a new discovery in the Kennett Library collection surfaced. Another scrapbook, this one functioning as an herbarium, was found as we were inventorying plant-related items in the collection. This scrapbook contained an inscription identifying its owner, who was none other than Marie Hansen—and, excitingly, the handwriting inside it matched with the samples taken from the architecture scrapbook and Greece photos! Taken in tandem with the other evidence compiled, my supervisors and I feel confident attributing these items to Hansen, and interpreting her life and times through their lens.

We were fortunate, in many ways, that Hansen was connected to fame, or else reconnecting her story to her creations might have been impossible. Sadly, not all items can be traced to their owners, and not all stories are recorded. But this tale exemplifies how important seemingly mundane items can be in connecting the past with future generations. The next time you’re cleaning out a relative’s attic and discover a dusty old album, take a minute to flip through it—you never know what stories are waiting to be told.