To David George Haskell, author of The Songs of Trees: Nature’s Great Connectors—our 2022 Community Read featured selection—trees underpin all life, playing an immensely important and lyrical role in human history and in modern culture. At Longwood, trees are the center of a network that connects us to the earth, to plant life, and to our past and future—they are the reason Longwood exists in the first place. The Songs of Trees is this year’s Community Read selection for Haskell’s poetic take on how human history, ecology, and well-being are intertwined with the lives of trees, but also because his descriptions of their ecology, both scientific and ephemeral, resonate with us here at Longwood. As a Longwood archivist, I’m often researching our trees—how they’re used, cared for, and what they mean to the people here. Their history presents itself in photos and records, but also antique candlesticks, brass tags, and rare books—and through these treasures we can help tell the story of our oldest residents at Longwood.

Longwood’s records of its trees date back to the Peirce family, who lived on this property for more than 200 years after George Peirce first purchased it in 1700. George Peirce’s twin great-grandsons, Joshua (1766-1851) and Samuel Peirce (1766-1838) were students of botany and natural history and began planting trees in an area of Longwood still known today as Peirce’s Park. Their 15-acre arboretum included specimens from their collecting ventures up and down the Eastern seaboard, and those ordered from early colonial nurseries. In the early 1900s, their great-grand niece Mary Woodward wrote of Peirce’s Park in an essay that remains in our archives collection:

“Many of the most stately cypress, spruce, firs, and magnolias owed their origin to the cypress swamps in Maryland and the Catskill Mountains of New York. The frail little withes were carried in the saddle-bags on a favorite horse of Mr. Peirce, who from time to time would have to dismount and by means of sprinkling their roots with water, kept them alive until they reached their destination. Thus, this beautiful spot, one of nature’s own, did not flourish by accident, but was the outcome of the work of years.” Her original essay is in the archives collection as well.

Chestnut Tree Grove in Peirce’s Park, as shown about 1913. Photo courtesy of the Hagley Museum & Library.

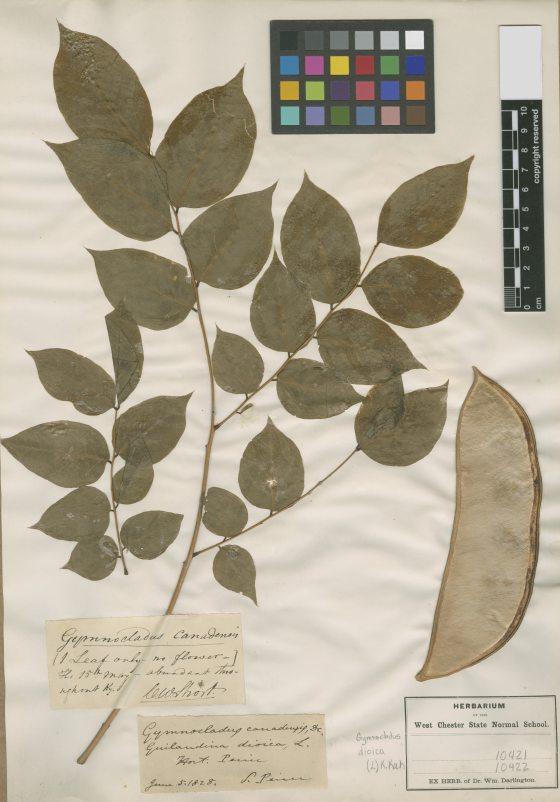

As the science of botany was developed in America, the Peirce collection of unusual trees was documented in a long-lasting way. Samuel Peirce contributed samples to William Darlington, the writer of Flora Cestrica, the first book recording the botanical species of Chester County, PA. Samuel Peirce’s personal copy of the 1826 book is in our rare book collection. Specimens of Franklinia alatamaha, Platycladus orientalis, and Gymnocladus dioicus (see below) from Peirce’s Park, preserved since the 1820s, are now in the collections of West Chester University. The scans we keep in the Longwood photo collections allow scholars to compare their current specimens to those of 1828.

Title page of Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees. Photo by Gillian Hayward.

Information about our long-standing connections with trees come from less scientific sources as well. In the archives object collection are several pairs of unreasonably large candlesticks that George Washington Peirce (1814-80), the son of Joshua Peirce, hand-turned on the lathe. George Washington Peirce lived in the family house, and was the person who opened Peirce’s Park to visitors, “who, when the park was in its prime, came any time and at all times and made themselves at home; content to enjoy what the owner, George Peirce, took pride in making beautiful for the eyes of the public.” The stewards of this land and its remarkable plants have been sharing its magic with the public for many years–it’s too good to keep to ourselves.

These candlesticks speak to the whimsical rustic aesthetic of the late-Victorian Peirce’s Park, but also attest to the size and maturity of his black walnut trees, as some candlesticks measure more than 6 inches in diameter.

Black walnut candlesticks made by G.W. Peirce, ca. 1870s. Photo by Alison Miner.

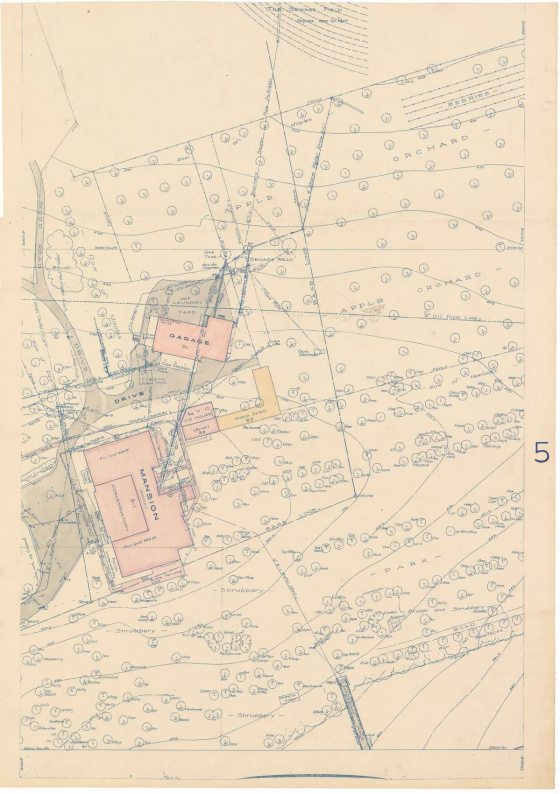

Longwood founder Pierre S. du Pont was enchanted with the centuries-old trees of Peirce’s Park and couldn’t bear to see them logged. When he bought the property in 1906 to save the trees, he also had plans to add more—a plan he followed through on beautifully. He planted more than 100 fruit trees in 1907 alone. In 1916, he hired surveyors to make a complete map of the property – a great effort that led to the creation of nine table-sized maps, detailing every tree. Today, these maps are invaluable for information on the types of trees the Peirces planted. We can also infer which trees Mr. du Pont added, and the ways in which he changed the landscape with those plantings. They show us exactly which of our trees are more than 100 years old, ultimately helping us piece together their history and their stories.

Influences on du Pont’s planning can also be inferred from his books we now have in the Longwood Library, including one of the oldest books in our rare book collection: Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber, published in 1664. John Evelyn’s book warned against the overuse of timber resources and is known as an influential very early work on forestry and sustainability. This conservationist perspective was still unusual in Pierre du Pont’s day, but has been common to the inhabitants of this land for centuries.

This topographical map of Longwood, dated 1916, shows the trees planted along the east side of the Peirce-du Pont House, the area now known as Peirce’s Park. The Peirce style of planting trees in straight lines can be seen clearly here – the trees at Longwood today are much less formally placed.

Influences on du Pont’s planning can also be inferred from his books we now have in the Longwood Library, including one of the oldest books in our rare book collection: Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber, published in 1664. John Evelyn’s book warned against the overuse of timber resources and is known as an influential very early work on forestry and sustainability. This conservationist perspective was still unusual in Pierre du Pont’s day, but has been common to the inhabitants of this land for centuries.

Title page of Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees. Photo by Gillian Hayward.

Historic photographs in the collection also attest to the heroic work of Mr. du Pont’s employees in creating the Longwood we know today. Some of the larger trees in our landscape are not survivors from the time of the Peirces, but were rather transported here as adults, at great effort, and with the help of trucks, tractors, and even helicopters. The English yew in the East Conservatory Plaza was found by nurserymen visiting old Delaware homesteads, and planted in 1930 at full size, and already more than 100 years old.

In this 1930 photo, the English yew is being moved from S.S. Deemer’s of New Castle, Delaware. This tree is a specimen from the famous Deemer Arboretum, a large part of which was moved to “Longwood”.

The copper beeches between the Conservatory and the Peirce-du Pont House were hauled into place by teams of men with trucks in the 1950s, and one was even flown in with a helicopter in 1999!

Planting beech trees in 1951.

Much effort was also expended in du Pont’s time to preserve old trees, too. When chestnut blight began to affect the trees from Peirce’s Park, du Pont took action to try to save them. He acquired a horse-drawn spraying cart so his workers could reach every tree. Sadly, the chestnut trees succumbed to the blight, but knowledge for fighting diseases in the future was gained

Worker with tree spraying machine, 1912.

Workmen repairing tree, 1925. Photo by E.P. Mullen.

When the Dutch Elm Disease hit Longwood’s American elm trees in the mid-20th century, Longwood’s arborists had more techniques to try to resist the disease. With care, they kept many alive through the 1980s. Today, only the elm by the Visitor Center remains, and our arborists work to keep it healthy and have propagated many young clones, in the hopes of increasing varieties that can endure Dutch Elm Disease.

To keep track of the status and health of individual trees, Longwood requires a robust system of record keeping. While information about Longwood’s trees was initially recorded on maps, in order to keep track of individual trees, it became clear that more documentation was needed.

To that end, Longwood’s Plant Records office was created in 1955 to capture information about our plants more systematically. Each group of new plants brought on to the property were assigned an accession number in a log book, and originally, a large card was made for the accession, then each individual plant within that accession got its own card with specific location, which was maintained by the gardener of that location. With at least two cards for each type of plant, it soon became the job of several people to track the plants on the property, and subsequently the index cards ballooned. Every time a plant in the garden moved or died, the gardeners would make a note on their card, send it to Plant Records where they would note that on their cards, and then send the card back to the gardeners. With the aid of a huge amount of labor, all the records were kept up to date.

Data processing in the Plant Records office, 1968. Photo by Gottlieb Hampfler.

It is clear why Longwood was an early adopter of a computerized record system for the plant records, which took place in the late 1970s, and then transitioned into a database. Our current plant records database includes more than 100,000 individual plant records, with 48,000 plant names and more than 60,000 accessions. These records are now tied to individual trees, so arborists and gardeners can note changes, themselves.

The connections between the trees and records are not just virtual, however. To aid in identification, inventorying and mapping, trees are given unique numbers and letters, and labelled with brass tags that record their scientific and common name as well.

A brass tree tag identifies a bald-cypress. Photo by Richard Donham.

Sometimes, despite our arborists’ best efforts, a tree must come down. In the past, a tangible memento was kept of large trees. In 1937, then-Chief Horticulturist John M. Johnson made a souvenir for du Pont—a gavel turned from the trunk of a large boxwood in Peirce’s Park. Holding this item in your hands today calls to mind how long the slow-growing boxwood must have been alive in order to get so dense. These days, in the case of large trees, sometimes weightier evidence is preserved. The arborists will slice a piece of the trunk, termed a “tree cookie”, to commemorate the tree and count its rings.

Gavel made of boxwood from Peirce’s Park.

From the maps on which they were first recorded … to the images that help us piece together their histories … to the physical evidence that shows us their exact age, our trees have many, many stories to tell. We are honored to be just a few of the many stewards of their stories, helping illustrate the people and plants here at Longwood, and the many connections that have been made—and have yet to be made—along the way.