Defined as the art of shaping plants, topiary can also be described as a life’s work. Rooted in the art and the beauty of working with living plants—which means waiting years or even decades for plants to take form—topiary takes time, patience, and skill to come to fruition. Here at Longwood, our Topiary Garden is not only a place of beauty, but an experience made possible by the many horticulturists who have shaped this beloved space for nearly a century. With 35 specimens and more than a dozen forms ranging from wedding cakes to spirals to birds, our Topiary Garden is much more than a collection of yews (Taxus)—it’s also a collection of stories told by those who have so expertly cared for it.

The art form of topiary goes back centuries, with the first literary description of topiary appearing from Pliny the Younger’s garden in Tuscany, Italy, in the 1st century AD. Topiary has traditionally been associated with formal or structured garden styles and is mostly seen in gardens of Europe, the UK, and Asia. There has never been a strong presence of traditional topiary in the United States, even with the beautiful topiary gardens of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, Green Animals Topiary Gardens (Portsmouth, Rhode Island), and Ladew Topiary Gardens (Monkton, Maryland) . As more plants moved indoors and the houseplant craze heightened, a revival period in the 1960s and 1970s occurred as more topiary figures became portable and popular among home gardeners. By bending wire and sphagnum moss, these topiaries can be created from any plant in any location by stuffing wire frames with moss and plants; this American adaptation of topiary is sometimes called “new” topiary.

An example of new topiary, reindeer frolic in the Topiary Garden during A Longwood Christmas in 2008.

In general, topiary today has no stylistic affiliation, unlike the Renaissance, during which geometric shapes like cones and pyramids and sculptural forms like animals and objects became very popular. In contemporary society, topiaries can act as formal and playful accents in the landscape, contrasting with nature’s shapes while sparking interest and curiosity. They can be shaped, made, and owned by anyone regardless of social class and status, thus allowing the home gardener, enthusiast, or amateur the freedom to enjoy.

Traditional topiary first appeared at Longwood Gardens in 1936 in a space originally used for a vegetable garden. Longwood founder Pierre S. du Pont built a 37-foot analemmatic sundial and surrounded the sundial with a horseshoe of yew (Taxus) hedges, as well as 11 domes and two cones in the shape of an ellipsis.

This 1930s aerial view of the Topiary Garden shows the original topiary hedge, domes, and cones arranged in the shape of an ellipse, covered in a blanket of snow.

Snow blankets the Topiary Garden in January 2022. Photo by Becca Mathias.

In 1958, Longwood purchased 30 large yew topiaries in six different designs from the Bayville, Long Island, New York estate of Mrs. Harrison Williams, who after her next marriage became the Countess Mona von Bismark. The topiaries were planted among the existing yews surrounding the sundial. More specimens were acquired in 1962 and 1971 from the Charles Fiore Nursery in Prairie View, Illinois, and from Taylor Arboretum in Chester, Pennsylvania, and the space was renamed the Topiary Garden.

Approximately 30 topiaries came from the Bismark Estate in Long Island, New York in 1958. Photo by Gottlieb Hampfler.

In 1980, five pieces created by Jack Hamilton, Longwood’s-then Topiary and Rose Garden Head Gardener, were moved into the display. Hamilton is credited for creating much of the forms we see in the Topiary Garden today. He sculpted the garden for nearly two decades from the late 1950s into the early 1980s, creating several impressive pieces such as a rabbit and an armchair with a table. Following Hamilton, Dave Thompson started as Head of the Rose and Topiary Garden in 1983, and worked to create a more uniform experience, slowly pruning the tops of the topiary so that they came to a point, thus giving them a stronger geometry.

Sometimes forms reveal themselves in unexpected ways. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the caretakers of the Longwood Topiary Garden added many whimsical pieces to the landscape, including one large, rounded shrub in which Thompson created a tail, thinking it resembled an animal. He added some eyes and the start of ears but couldn’t tell if it was more a dog or bird, until a group of young children came into the garden one day and excitedly declared it “Snoopy’s dog house.” A swan made its debut in the 1980s, but unfortunately succumbed to drainage issues, hot summers, and heavy snows.

In this June 1988 photo, Section Head Jeff Lynch, Section Head Dave Thompson, Senior Groundskeeper Harry Osborne, and Equipment Operator Wayne Bramble (left to right) plant a topiary swan on the west side of the Topiary Garden. Photo by Larry Albee.

Thompson had many helpers along the way, and he humbly credits the crew also known as the “arborist group.” Two members of the arborist crew who had much to do with the original shapes of larger yews were Leo Barbacovey and Charles Antes; Barbacovey created the ornamentation on the original large “gumdrop” shrubs (also known as domes today) which were a part of the Yew Garden before the topiary were added in the late 1950s.

In this 1980s photo, arborists Harold Taylor, Charles Antes, Rick Patton, and Burnett Groves (left to right) take a break from pruning in the Topiary Garden. Photo by Dave Thompson.

Thompson also credits a student assigned to his garden at the time: Tim Jennings. Now a senior horticulturist who oversees Longwood’s Waterlily Display, Jennings worked with Thompson in the Topiary Garden as a student during his time in the now-Professional Horticulture Program (1986 to 1988) and then as a full-time gardener in 1989.

Today, Outdoor Landscape Manager Troy Sellers oversees the Topiary Garden. In the early 2000s, following wet soil conditions in the 1980s and 1990s that led to the decline of several topiaries, Sellers and Outdoor Landscape Manager – East Section Roger Davis created a replacement plan to ensure the Topiary Garden will always be full and lush. “We have at the nursery a topiary block, which is basically back-up plants if something happens,” shares Davis. “They’re not perfect, but rather rough geometric shapes that can be moved in and added to over time if needed.”

The 1997 A Longwood Christmas display featured this new topiary peacock made from moss, wire, and plants.

In 2015 and 2016, the Topiary Garden was one of the locations for the Nightscape by Klip Collective projections. Photo by Hank Davis.

Today’s Topiary Garden is not only an historic collection of topiary but a canvas for ever-evolving art, to be appreciated on both grand and detailed scales. The forms themselves are massive in scale, and if you look closely at the original forms of the 1930s collection, the structure of the branches themselves can also be appreciated. “Being able to see the structure and branches on the inside of each specimen reminds you it's a plant,” shares Davis. “It's a living thing.”

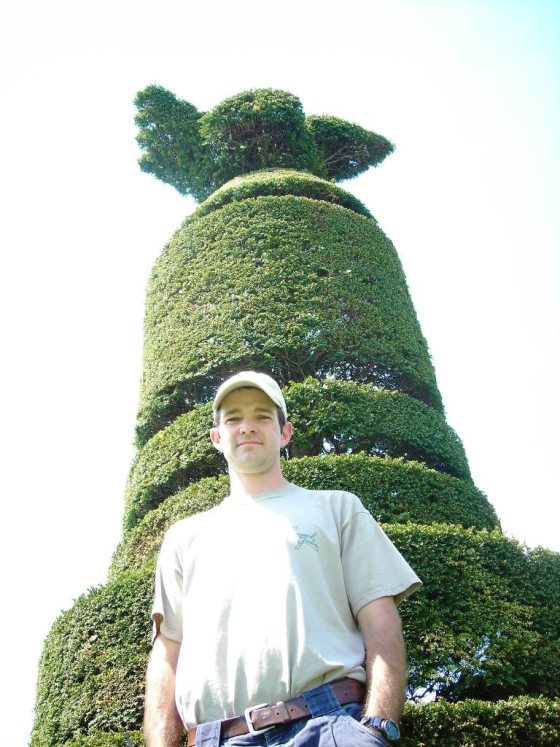

Longwood Outdoor Landscape Manager – East Section Roger Davis stands in the Topiary Garden in this April 2007 photo.

Many topiary techniques are practiced by gardens and gardeners worldwide. At Longwood, all of our topiaries are sheared with electric hand pruners and various aids like lifts and levelers help assist our gardeners in cutting straight lines and reaching tall yews. Thompson shares a tip: “There is one technique that is extremely important. Begin your cutting on the top edge and get that top edge back to where you want it before you ever touch the bottom. What happens is, when you cut the bottom back to where you want it, it is now almost impossible to cut the top far enough back to give the shrub any kind of bevel or straight edge.” Everybody shears a bit differently and has their own technique, which often makes topiary gardening both a challenge and an opportunity when translated from gardener to gardener.

Outdoor Landscape Manager Troy Sellers, who currently oversees the Topiary Garden, shears the garden in 2013. Photo by Steve Fellows.

Although Davis no longer cares for the Topiary Garden, he has devoted more than a decade to the artform and continues to shape topiaries at his home landscape and experiment with new forms. When attempting to create whimsical shapes, Davis shares that “they typically get more whimsical as they age. Over the years and as branches age, they do not hold up as much, so organic and whimsical shapes are a little easier to make than formal shapes.”

The Topiary Garden is viewed from the Rose Garden in this October 2021 shot. Photo by William Hill.

Throughout the decades, the Topiary Garden at Longwood has been a constant reminder of the past, a sense of permanence and timeless appeal, dressed in a carpet of green and graced by geometric and whimsical forms. The immersive experience of stepping down into the Topiary Garden and standing next to yews more than 100 years old transports guests to the classical era of Rome and Greece or the formal gardens of England and France—and it tells the stories of all who have cared for it. Along with the work and stories of the garden’s caretakers, the beauty of the garden truly lies in its uniformity, formality and mystery, sprinkled with a dash of humor. It has the power to transport guests to another world—one with delight, magic, and fantasy—and serves as reminder of a long-held artform formed and shaped throughout the centuries, as well as provides inspiration for those starting and caring for their own topiary.

Editor’s note: Join us as we celebrate World Topiary Day along with gardens around the globe. Founded in 2021 by Levens Hall and Gardens (Cumbria, UK)—home to the oldest topiary garden in the world—this May 12 occasion (which we’re celebrating May 12, 13, and 14) recognizes the beauty, art, and joys of topiary. Explore our Topiary Garden’s whimsical forms, lean how we’ve meticulously trained the yews over many decades, and get an up-close look at the 35 specimens throughout the garden. Horticulture experts will be on hand from 10 am to 4 pm each day to answer your topiary questions.