Very close to Route 1, just south of the entrance to Longwood Gardens, stands a 19th century farmhouse that silently bears witness to an illustrious history ultimately connected to today’s Longwood Gardens. Now known as the Cox House, after its most notable former owners, this farmhouse has connections to the early Quaker settlers of southern Chester County, including generations of farmers, 18th century plant collectors, and 19th century social justice reformers. The house also holds the stories of the enslaved people who passed through the house and the surrounding farmlands, assisted by its inhabitants and other allies on their escape to freedom.

Early Settlement & The Peirce Family

Up to the formation of a colony in 1681 by William Penn, the Brandywine Valley was populated by Lenni Lenape. Their approach to nature shaped the landscape, wildlife, forests, and meadows. It is within this landscape that the Peirce family arrived from England when they purchased a Penn land grant in 1701. After settlement by the Peirce family and other Quaker farmers in the early 18th century, some Lenni Lenape continued to live nearby, while many migrated further west to escape encroachment on their homeland. The Peirces, like other European settlers, slowly began to impose their own ideas onto the land by clearing, building, and introducing crops and livestock enclosed by fences. On the 402 acres purchased from William Penn, George Peirce and the generations that followed would establish a homestead that gave rise to impressive and varied legacies.

The first two generations of the Peirce family began farming the land and built what we now know as the Peirce-du Pont House. The house, and the adjacent arboretum (which came to be known as Peirce’s Park) originally planted by George’s plant-collecting great-grandsons, Joshua and Samuel Peirce, is where we say the Longwood story begins. Indeed, this swath of land and its trees inspired our founder, Pierre S. du Pont, to purchase the property that was to become Longwood Gardens, setting off an entire chain of events that leads to the great garden of the world that we are today.

But the Longwood story has another branch, extending to the Cox House (built on the southern portion of George Peirce’s original 402 acres) through George’s great great granddaughter, Hannah, and leading to a significant chapter in American history and the fight for freedom, human rights, and social justice.

The Longwood Farm & The Cox House

Who built the Cox House and whether or not another farmhouse existed prior is unknown. One later archival source credits Jacob Peirce (1761-1801)—brother of Samuel and Joshua Peirce, who together created the 19th century arboretum at Peirce’s Park— as the builder of the Cox House. However, there is little other archival evidence to substantiate this claim. This southern portion of the Peirce Farm passed from Caleb Peirce (1727-1815) in 1815 through multiple other Peirces until it was acquired by Jacob Peirce (1790-1857)—Hannah’s brother—in 1826. In 1829 John (1786-1880) and Hannah (1797-1876) Cox purchased two tracts of farmland. A new generation of Peirces (through Hannah) continued to farm the land as they had for more than 100 years, while at the same time a new family name, Cox, began a new era for the property.

A Changing Landscape: The Cox House

19th century photograph of Route 1, then a quiet dirt road, near the Cox House and Longwood Farm looking east. The house’s roof is clearly visible between the trees to the left.

The Longwood Farm, pictured in the late 19th century viewed looking north. The Cox House is behind the trees to the left of the granary building. Notice the long strip of trees lining the roadway and enclosing the house and granary buildings.

The Cox House, c. 1920s. By this time the roadway (Route 1) had been widened and improved. The farmlands separated from the house and the era of the property as a working farm was ended.

The Cox House, present-day. Photo by Carol Gross.

After becoming the owners, John and Hannah Cox began to raise a family on their prosperous farm—the Longwood Farm, interestingly, the source of Longwood Gardens’ name. Over the next 50 years of marriage and rural farm life, the Coxes raised six children. In addition, John and Hannah Cox were religious and social justice activists who were leaders in the region and helped to found two local institutions aligned with their beliefs. They believed in the equality of all humans and worked their entire lives in service to this ideal. They sought a spirituality sometimes beyond the bounds of traditionally defined Quaker faith of the time. Both were deeply involved in Progressive social movements of the mid-19th century, including regional and national organizations for abolition, women’s rights, and temperance. Further, they put their lives, property, and prosperity at risk by using their farm as a haven for escaped enslaved persons and actively transported these freedom seekers to other safe houses along the Underground Railroad.

John and Hannah Cox illustrated in History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania by R. C. Smedley (1883).

The Longwood Progressive Friends Meeting House

In 1853, following other Progressive Quakers in the Northeast and Midwest United States, the Coxes—with other likeminded, local Quakers and national leaders of reform movements—created a new religious society at the Old Kennett Meeting. This new Quaker meeting—Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting of Progressive Friends (locally known as Longwood Meeting after the Cox’s Longwood Farm)—sought to break free of the traditional Quaker discipline in service to humanity. The only requirements for membership were attendance and a desire to engage with social reform ideas.

Sharing the small meeting house with a traditional Quaker meeting quickly proved to be problematic and sometimes violent. The second annual meeting in 1854 of the Progressive Friends resulted in a skirmish with members of the Kennett Meeting and had to be relocated to a much smaller building in nearby Hamorton village to the east. The Progressive Friends needed to establish a separate home if they wished to discuss, worship as they wished, and campaign for reform. Funded by donations, in late 1854 John and Hannah Cox sold a small parcel of their farm to the new religious society. Work quickly commenced to erect a building. By May 1855, the Progressive Friends gathered in their newly constructed meeting house for the first time.

The initial two decades of the meeting’s history is the most active, and the annual meeting frequently attracted very large crowds—upwards of a couple thousand people—during the three-day meetings. Attendees would hear sermons, prayers, lectures, and—very rare for a Quaker meeting of the time—live music. The more frequent quarterly and monthly meetings were much more local affairs with smaller crowds to review organizational business or to hear the many invited speakers. After the Civil War, although the fire of abolitionist zeal diminished, other reforms like a woman’s right to vote remained to be accomplished. The meeting endured until 1940 when it was dissolved, and the property sold to Pierre S. du Pont. The building was to be used for classes and meeting space for groups, like local Boy Scout troops. Today the property is still owned by Longwood Gardens and is occupied by The Chester County Conference & Visitors Bureau.

Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting of Progressive Friends, also called Longwood Meeting, 1865. John and Hannah Cox are near the center of this group of Progressive Friends that includes William Lloyd Garrison, one of the most famous abolitionists in the United States.

The Longwood Cemetery

At first glance, the Longwood Cemetery across the street from the Progressive Friends Meeting House might seem like a churchyard cemetery. Together they form a picturesque landscape. However, the two organizations were separate, albeit both formed by many of the same Quakers, including John and Hannah Cox. The Longwood Cemetery was envisioned to provide a beautiful, final resting place for the community—regardless of race or the ability to pay. The original bylaws of the Longwood Cemetery Company enshrined these Progressive Quaker ideals into the fabric of the modest cemetery company.

In 1855 John and Hannah Cox sold 2 acres of their farm to the newly formed Longwood Cemetery Company. Then again in March 1885 a bit more of Cox’s farm was sold to enlarge the cemetery by Jacob P. (1824-1897) and Hannah B. Cox (1825-1887)—one of John and Hannah’s sons and his wife. This second purchase included Jacob and Hannah B.’s own house to be used by a sexton or caretaker (after the death of his mother, Jacob and Hannah moved into the main Cox House).

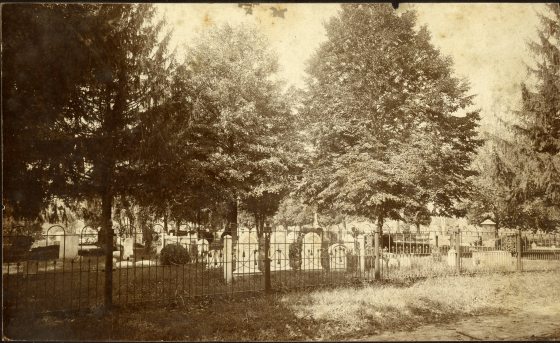

Late 19th century photograph of the Longwood Cemetery showing a decorative iron fence and lush plantings of trees and shrubs.

Longwood Cemetery today. Photo by Hank Davis.

The Longwood Cemetery Company has survived and became the final resting place of many of the original Progressive Friends (including John and Hannah Cox and most of their children), fellow station masters of the Underground Railroad, local residents from Kennett and surrounding areas, and many people who lived in and built Longwood Gardens from the gentleman’s farm to grand estate of Pierre and Alice du Pont finally into a public garden. In 2018, Longwood Gardens acquired the cemetery to protect this part of community and Longwood Gardens’ history.

The acquisition reunited the cemetery and meeting house with the existing remnant of the historic Longwood Farm, securing the enduring legacy of the Cox family and their progressive ideals. For Longwood Gardens, the connection brings together a larger story about the land and the family whose actions laid a foundation of both horticultural excellence and a more equitable society.

Editor’s note: The first image that appears in this blog post is of the Cox House in the last half of the 19th century.