Since owning the Longwood Cemetery in 2018, we have been working to understand the many layers of history contained in this relatively small parcel of land and its meaning to both the Longwood Meeting House (sometimes also called Longwood Progressives Friends) and the nearby Cox House. In a previous blog post we described the rich connection these properties have to Longwood Gardens through the Peirce family—early Quaker settlers who made an impact in the region in various ways, including family members who were Underground Railroad station agents. As we continue to immerse ourselves in the history of the Cemetery and its place in southern Chester County past and present, we develop a deeper understanding of the mid-19th century context in which the Cemetery and Meeting House were founded, so that we can better share those stories. With the start of Black History Month, we began sharing more on the members of the Black community who assisted an uncountable number of people in finding freedom from the great horrors of enslavement, and their connections with the Cemetery and Meeting House.

Critical Groups to the Underground Railroad

While not well documented, a critical group to the Underground Railroad were African Americans who were free as a result of Pennsylvania’s 1780 emancipation law, as well as those who had escaped bondage in the south and eventually settled in southern Chester County. Together, members of the Black community and local Quaker activists risked their lives and their livelihoods to help find freedom from enslavement as part of the Underground Railroad. A recent National Park Service National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom nomination concludes that in our immediate area, many hundreds—if not thousands—of enslaved people were assisted and guided to freedom by a dedicated group of agents and ardent abolitionists, including a number of Quakers. The Longwood Cemetery holds the documented remains of several of those Quaker activists who worked as a part of the Underground Railroad. Many, if not most, of the African American burials of this era, however, were unmarked. But through ongoing exploration of Underground Railroad documentation—which is frequently difficult to navigate and today mostly appears in letters held in archives and libraries—and through important writings by local experts, we can continue to piece together the many facets of this story related to southern Chester County—and the many people involved.

Of what we do know, a walk around the Longwood Cemetery is indeed a walk through history as one passes by the graves of John and Hannah (Peirce) Cox, Castner Hanway, and at least 32 others who were active allies to enslaved people seeking freedom. While we may never know everyone involved, the documented Underground Railroad station agents in the Cemetery include Lydia and John Agnew, Eusebius Barnard and his family, Hannah Darlington, Rebecca and Harlon Gause, Alice and Thomas Hambleton, Rachel (Peirce) and Robert Lamborn, Dinah and Isaac Mendenhall, Isaac and Thamazine Meredith, Mary and Moses Pennock, J. William Thorne, and William Webb.

The Longwood Cemetery grave of Underground Railroad station agents Isaac and Dinah Mendenhall. Photo by Hank Davis.

The Risks of Activism

This activism came with great risks—both for members of the Black community and for Quakers. Threats of violence were extreme and very real. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act made assisting the escaped a federal crime. Imprisonment, fines, and property seizure all were legal options by the authorities. Violence from neighbors could wreak havoc to property and risk personal injury especially from local gangs intent on harassment or seeking rewards for the escaped. Mob violence could take an even more sinister turn when aided by government officials. One such example is the burning of Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia after the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, which was overseen by the Philadelphia mayor. The risk for Black people assisting the escaped were even greater—including kidnapping and enslavement (or re-enslavement) for themselves and their families.

In southern Chester County, there was a constant threat from slavecatchers seeking those who had escaped enslavement and kidnappers prowling for those to trick or kidnap into enslavement. One incident in Christiana, Pennsylvania in 1851 involved both Black and white community members, including Progressive Friends founding member Castner Hanway.

This 1850 woodblock depicts the Christiana incident involving both Black and white community members, including Progressive Friends founding member Castner Hanway.

The locals, including Hanway, responded to an alarm of a federal agent and slavecatchers in the area. Upon learning the nature of the violence, Hanway refused to assist the white attackers or the federal agent. To repel the attackers, the locals—including many free Blacks—defended their besieged neighbors, which ended in the death and wounding of some of the attackers. A total of 38 people involved, including Hanway, were arrested and charged in federal court for violating the Fugitive Slave Act, but none were convicted. Even in the face of these risks, the work of the Underground Railroad and abolition continued.

At times even the Longwood Meeting House itself was used as a safe haven, as is in the case of Harriet Sheppard and her five children in 1855 fleeing from their enslaver in Kent County, Maryland. One particularly remarkable event that tested Garrett’s network was the “Cambridge 28.” In October 1857 a group of enslaved persons, including several children, made their way from Dorchester County, Maryland. Black abolitionist William Still informed Garrett that the group was in Centreville, Delaware and needed assistance to continue northward. They were attacked with clubs by local white community members, but managed to defend themselves. The incident drew unwanted attention in their direction, and they needed to move farther north quickly despite the severe weather of late October. Garrett separated the group and several were directed to retreat to or find safety at the nearby Cox House. Eventually many in the original group made it to St. Catharines, Ontario, to meet up with friends and relatives from Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

The Black community of southern Chester County grew steadily throughout the 19th century and represented a significant presence, forming villages, owning land, and building houses, churches, cemeteries, farms, and schools. Lincoln University, the second oldest Black college in the United States, is a direct result of the work of free Black property owners living in the village of Hinsonville as described in the book Hinsonville, A Community At The Crossroads by Marianne H. Russo and Paul A. Russo.

Hosanna Meeting House, near Lincoln University. Founded by free Blacks who had settled in this area, it was first known as the "African Meeting House." A station stop on the Underground Railroad, its many visitors included Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. It was formally organized in 1843 as an African Union Methodist Protestant church. Photo by Hank Davis.

Learning these Stories

How do we know such stories from such a secretive, clandestine network? Any such evidence itself presented a risk and could (and certainly would) be used against the agents and the escaped alike. Documentation of the Underground Railroad is frequently difficult. Fortunately, two important books from the 19th century exist to help tell the story locally: R.C. Smedley’s book History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and Neighboring Counties in Pennsylvania (1883) and Still’s The Underground Railroad Records (1872). Amazingly, Still’s book is a compilation of his interviews with each person he assisted along the Underground Railroad, as he wanted to document the facts of their lives and stories of their harrowing journey to freedom in the hope of reconnecting families broken apart by slavery. Remarkably, Still himself discovered his own brother—separated by decades—during one such interview.

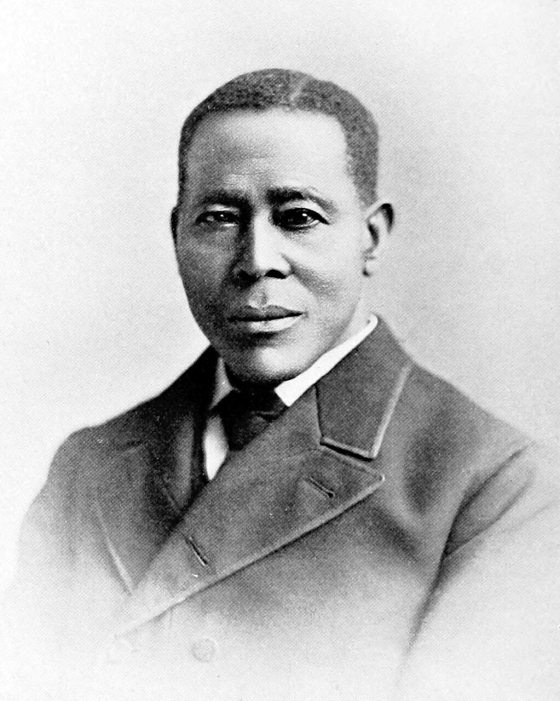

William Still, abolitionist and author of The Underground Railroad Records (1872), a compilation of his interviews with each person he assisted along the Underground Railroad.

Southern Chester County is steeped in the history of the Underground Railroad and the struggle against the evil of slavery, and we are humbled to have this history represented right at our entrance gates. The Longwood Progressive Friends Meeting House, the Longwood Cemetery, and the Cox House—owned by Longwood Gardens and acquired over the years to secure this important historical legacy—help tell the story of those who risked their lives and livelihoods in the struggle for freedom in Chester County. They stand in testament to that struggle and serve as a reminder of the immense role and activism the Chester County community played in the 19th century.

Visitors wishing to experience the history of the Longwood Cemetery are welcome to do so daily from 8 am to dusk, and can follow a self-guided tour to learn more about the Cemetery and those buried on the grounds.

Together, a number of local and regional organizations are working to better understand—and share—the story of the Underground Railroad in southern Chester County. Kennett Square-based nonprofit Voices Underground, Lincoln University and its Center for Public History (created in partnership with Voices Underground), the Kennett Underground Railroad Center, the Kennett Heritage Center, and Longwood Gardens continue to delve into the area’s African American history and its connection to the Underground Railroad through further understanding, research, and storytelling.

Editor’s note:

Locally to Southern Chester County, amateur historians Mary Dugan and Frances Cloud Taylor dedicated a large portion of their lives to keeping alive the local stories of the Underground Railroad. The magnitude of historical importance has attracted some significant scholarly attention locally as well. The work of Christopher Densmore on the history of the Longwood Progressive Friends Meeting and William Kashatus on Chester County’s role in the Underground Railroad have advanced our collective understanding of this local history. William Still: The Underground Railroad and the Angel at Philadelphia (2021), by Kashatus, closely examines the life of Still and his interviews for further clues and insights. Other historians continue to expand our understanding beyond Chester County. James Oliver Horton and Lois Horton have greatly advanced this historical perspective of abolition efforts by the 19th century Black community. Cheryl Janifer LaRoche employs an archeological approach to reveal and inform a greater understanding of the Underground Railroad and the role of free Black communities. Historical research continues with more of the Underground Railroad’s story yet to be uncovered.